Toward Annihilation: House of the Dragon and Anti-War Television

In season two of House of the Dragon, every move is a sacrifice.

Duty is sacrifice. All men of honour must pay its price.

These are the opening words of the second season of House of the Dragon, spoken by a Stark lord about inducting a boy into serving the endless maw of war, in this case the war of the Night’s Watch against the wildlings, long-since divorced from its gleaming true purpose. A son is sacrificed to a cold, pointless life, toiling to find deserving blood to shed.

It’s a strange choice for an opening sequence, considering no one in House of the Dragon joins the Night’s Watch, it has no impact on the plot, and we don’t even get to spend more than a scene with Cregan Stark. Our understanding of the Watch, as faithful HBO viewers, isn’t particularly nuanced. Game of Thrones never spent very much time complicating the institution (actually, it very much liked to portray the wildlings as mindless cannibals). Joining the Watch should seem like a fairly normal, amoral practice, even with some cursory knowledge of the books. It shouldn’t be particularly meaningful for some random kid to get drafted into a chilly penal colony— at least not meaningful enough to open a season of television.

But Cregan says “offering”. He says “sacrifice.” The imagery of the ‘choosing’, with its bag of white stones— and one black, marking the chosen— is identical to that of Shirley Jackson’s Lottery. It invokes the selection of a blood sacrifice, all in the hardened name of duty, hidden in the neutralizing language of oaths. The mundane accepted practices of this world, it is revealed, are sinister, and hunger for bodies.

“This is not a sentence,” Cregan says, “but an honour.”

In A Song of Ice and Fire, the Wall is alluded to as a sacrificial site many times over. The seventy-nine sentinels, deserters from the Watch, are said to have been sealed inside the Wall still alive, eaten by the ice. Below the Nightfort grows a weirwood gate, a great maw opening and closing— weirwoods being sites of blood sacrifice, many centuries ago. Ygritte spits, “This Wall is made o’ blood.” It is a hinge of the world, says Melisandre, and we must know what those hinges are oiled by.

It’s not the only hinge. Craster’s sons are left on a snowbank, to feed the cold blade-mouths of the Others. A young Sam Tarly is submerged in a bath of blood. To queen her is to kill her, Illyrio purrs, the kingmaker.

When Blood and Cheese break into Helaena’s rooms, they force her to choose a child to kill. Erryk falls on his sword in absolution. Alicent makes a desperate bid for freedom, and in doing so, must doom her son to execution. All must choose— so says the marketing campaign.

Duty is sacrifice. But sacrifice of whom?

In his book War and Film, James Chapman posits that there are three types of war film: those positing war as spectacle, war as tragedy, or war as adventure. But TV is a little weird in that sense— it has to approach it differently, it can’t be bottled like that as such. In some ways, the struggle and the triumph of the war film is that to succeed they must have a perspective singular enough to be confined, temporally, to its typical length. In contrast, TV is a medium of progression, and its approach to themes can be more tangled and exploratory.

House of the Dragon takes full advantage of this, beginning long before the war is even an inkling in the characters’ mind, showing war as a political game first and foremost, just words, until it isn’t. Its origins are systemic more than they are necessarily personal. It spans decades, follows each character as they are reared, as they grow up in this poisonous, cultish society and then rear children of their own. It’s a sociological story! Game of Thrones was too scattershot and wide-ranging to be able to say something coherent ‘about war’, but from its premise House of the Dragon has been laser-focused: a full taxonomy of a war, from its bloody, malformed birth to its growing tensions to its all-out explosive spectacle to its bitter, miserable end.

Because House of the Dragon’s second season ostensibly portrays a war, but it doesn’t exactly “portray” a “war”. Outside of its fourth episode, there are no scenes of full-scale battle, only aftermath, or build-up, or the odd distanced village-burning. Of course, battles are expensive to film— especially those involving several CGI dragons— but this is a very deliberate choice.

This conspicuous absence of “war scenes” is most notable in episode three’s titular Battle of the Burning Mill, which begins with a territorial squabble. The young members of the small houses of Blackwood and Bracken, long-since locked into millennia of petty conflict, meet at their contested border. One house is sworn to Aegon and the Greens, the other to Rhaenyra and the Blacks, so nominally, they are “at war”— but that’s not really what the fight is about. They fight because that’s all they know how to do, the only way they’ve been taught to act. To not fight would be to disparage their precious chivalric “honour”. A sword is drawn, then—

We cut away.

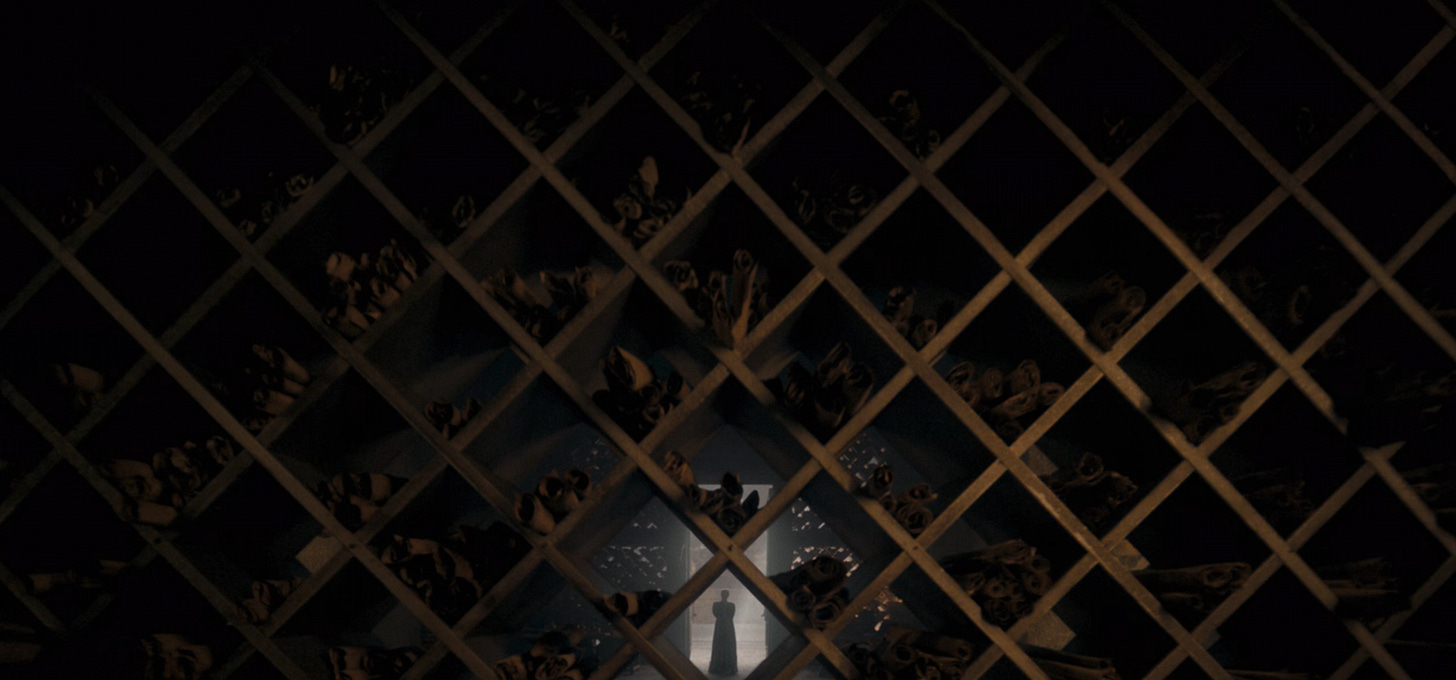

We see a corpse, set against crude blackness that reveals itself to be hundreds of bodies stacked across the field. The mill burns in the background, their treasured territorial prize, ash now. Pointless. Crows feast on the flesh of the bright boys we just saw smiling. Who killed whom? When were the levies summoned? Who burned the mill? Does it matter?

The choice to hard cut to the piles of already-dead bodies rather than show the battle itself can’t just be explained away by budget cuts or narrative simplification— it’s an active filmmaking decision. It eliminates any chance for the audience to find this moment cool or epic or glorified— we are left to witness only the direct result of war, of any war, rendered so disturbing it revolts against being prettily narrativized. Bodies, blood, dirt. This is what you wanted, right? Okay, then look at it, really see. After all, this battle is a microcosm of the entire conflict, the raw shuddering pointlessness of it, the litigation of petty interpersonal disputes requiring the bodies of hundreds and thousands of their marginalized levies, who could care less if a dragon was red or gold, who burn nonetheless.

It is made very evident that the instigating parties are young. Still children.

It is the fourth episode of the season, The Red Dragon and the Gold, which is the true ‘battle episode’, the big HBO spectacle. Here the violence is turned operatic, even apocalyptic. To be frank, it looks straight out of Dark Souls. The dragons dance like the big hulking beasts they are. There’s a strange thrill to it that’s quite rare in this show, so draped in its dour tragedy.

It begins with a montage of preparations, all while Rhaenyra reveals to her son Jace her hidden motivation— the prophecy her father told her about, of a Protector, born of their line, meant to unite the Seven Kingdoms against a common enemy. She believes— he believed— this prophecy concerned her. But her words are muddled and perplexing, deeply vague. Who is the common enemy? She doesn’t seem to know. A dream, a song, a nameless cold and dark. But we know how this ends. There is no uniting, and she is no saviour of the realm. There is no purpose, no protector. The prophecy, already turned to pretty gibberish, is lost to time.

“The horrors I have just loosed,” she says, as if trying to convince herself, “cannot be for a crown alone.”

And we cut to battle. Scores of arrows, hundreds dying on a plain-featured overcast field belonging to an unremarkable, pointless keep. Dragons appear in the air, alternating between shots where they are portrayed as distant, threatening fighter jets— from the soldiers’ perspectives— and closer, sweeping camera angles that revel in their graceful, dangerous dances… until suddenly the claws come out, and we remember they are bodies too, gouged and dripping boiling black blood and squealing like gulls. The soldiers on the ground attacking the keep are filmed with a strict left-to-right directionality, but the direction of battle becomes confused in the air. The rules don’t matter anymore, and that’s the most frightening part.

Vhagar, the largest dragon of them all, is not filmed like a dragon as much as she’s filmed like a movie monster— a kaiju, or King Kong, or even the supermassive alien from Nope. She’s a horror creature, almost eldritch in her largeness, blending into nature like a moving mountain, camouflaged in the greenery. What makes a horror monster scary is how sheerly unstoppable they are— when they show up, there’s nothing you can do, you can’t run, you can’t hide, so it is the threat of their appearance, rather than their actual violent acts, that holds the most suspense and engenders fear. Trees rustle; something thumps the ground. Then just the tips of her wings crest above the tree line like the shark fin from Jaws. She’s a natural disaster more than she is a conscious being.

Vhagar is transformed into an avatar of war itself, a great maw that burns and flattens everyone in its path, friend or foe, innocent or actor, mutilating the countryside. She’s ridden by one of the characters who gets closest to being a truly amoral sociopath, Aemond. Pseudo-intellectual he may be, Aemond at war moves on pure id, acting without restraint because there is no need, brutalizing his brother and his dragon out of the sexual humiliations of his past and the ambitions of his future.

In fighting Meleys, Vhagar is brought crashing to the ground. The impact knocks out our main point of view on the field, Criston. In flashes we get slow-motion shots of Vhagar’s inscrutably massive talons crushing men of all sides of the battle, emerging from the dust like a demon out of hell. When Meleys hits the ground she explodes, her body turned into a bomb strike. Bodies are burned and tarred. The entire world has gone grey with smoke, the field flattened. In this way it begins to borrow from the filmed aesthetics of the First World War, described by James Chapman as “devastated landscapes with ruins of buildings and broken tree trunks, tangled fences of barbed wire and, above all, mud.”

But there is something unmistakably apocalyptic about it, too, the layers of fine grey dust and the unbreathable air bringing nuclear winter to mind. Everything has been obliterated completely. It’s spectacle, but a desolate, tragic one, mired in death and horror from every angle, colourless and leached. The compositions are lonely and bleak, but beautiful, even that of a soldier who, when touched, collapses into burnt bones and dust. A commander yells, “Into the breach!”, invoking the famous speech from Shakespeare’s very own war story, Henry V, which is fascinated with the mechanics of a happy youth’s transformation into a hardened warrior prince (topical!)— what one must choose, what one must sacrifice.

King Henry’s speech at the siege of Harfleur delves into that sacrifice, into how a man must prepare himself for battle. The monologue can be played many ways, and certainly it has been— frightened, patriotic, bloodthirsty. But to me, I’m most affected by its neat, exhaustive catalogue of a warrior’s body. “Stiffen the sinews, summon up the blood […] lend the eye a terrible aspect; Let pry through the portage of the head / like the brass cannon; let the brow o'erwhelm it […] Now set the teeth and stretch the nostril wide, / hold hard the breath.” These read not as bodily excitement but as contortions, painful and malformed. I might go so far as to call it an expression of body horror.

Bodies come up repeatedly in House of the Dragon season two, and not just at war. This world seems to reduce everyone to bodies, and what those bodies can provide— women as child-bearing machines, and men as fighting machines, nothing more, nothing less. Sacrifice your life on either the birthing bed or the battlefield, controlled by the whims of husbands or fathers or kings, stripped of agency, for the sake of your gendered “duty”.

Not a sentence, but an honour.

After the killing of the child Jaehaerys, Otto Hightower demands a public spectacle, parading not only his body but those of his mother and grandmother, turned to political images, abstractions. “With your child’s blood we bought their approval,” he says. “With your mother’s tears we made a bitter sacrifice.” No one lays it out any plainer.

Every interaction in this season takes on a sacrificial connotation, subject to violent power dynamics. Characters refer to themselves as “tools”, only as useful as what their bodies can achieve. No one is in control or has agency over their bodies, their images. Criston Cole shuffles around like a zombie. “I do not wish to be a spectacle,” Alicent asserts, but must submit anyways. This war has turned them all into wights. The colour grading of the show has this certain low-contrast blue-black wash to it; the few times the lighting creates any sharp contrast or painterly chiaroscuro is to silhouette the characters, not illuminate them. Within the walls of each of their castles, the characters’ images are flattened, turned to shadows, paper puppets.

The shot compositions serve to trap the characters, too; this stylistic flourish is especially blatant with Alicent and Rhaenyra, as the show’s two most prominent women, who are so brutally trapped by their fates and marginalized by the men around them. They cannot escape cage-like frames; columns or windows box them in on all sides. Their shifting levels of freedom of choice in this war directly correspond to the shots that frame them. By the end of the season, it’s Alicent who finds herself free, silhouetted against a massive open sky, and Rhaenyra is trapped in interlocking shelf frames, holding the scrolls of histories that will eventually trap her, too.

Out of all the filmmakers who’ve tackled the ‘war film’, House of the Dragon oddly reminds me of the work of Terrence Malick— if not in filmic technique then in temperament. His is a cinema of bodies, above all else. There’s such a strong physicality to his work, as if touch is all that matters. The Thin Red Line (1998) follows a company of U.S. soldiers on the Pacific Front of World War II, pushed towards gruelling lines of attack by their commanders, elliptically following their suffering and their inflicting of suffering. It’s hard to describe it succinctly; producer Bobby Geisler managed it this way: “Malick’s Guadalcanal would be a Paradise Lost, an Eden, raped by the green poison, as Terry used to call it, of war. Much of the violence was to be portrayed indirectly. A soldier is shot, but rather than showing a Spielbergian bloody face we see a tree explode, the shredded vegetation, and a gorgeous bird with a broken wing flying out of a tree.”

Every character looks like they’re trying to crawl out of their bodies, constantly wrestling with the violence they are asked to wield. A dying Japanese soldier speaks in voiceover, buried in dirt with only his face visible: “Are you righteous? Kind? Does your confidence lie in this? Are you loved by all? Know that I was, too. Do you imagine your suffering will be any less because you loved goodness and truth?” (Exhausting, wasn't it? Hiding beneath the cloak of your own righteousness?)

The film wonders openly if the destruction man has wrought is just a part of nature’s violence, or something created, specific to mankind. But it is suffused with the dynamics of power, the doomed and horrific intrusion of “civilized” structure onto unblemished nature. A new captain is assigned to the company and attempts a rousing speech. “I prefer to think of myself as a family man, and that's what we aII are here, whether we Iike it or not. We are a family. I'm the father. Guess that makes Sergeant WeIsh here the mother... That makes you aII the children in this family. Now, a family can have only one head, and that is the father. Father's the head, mother runs it. That's the way it's gonna work here.” He invokes patriarchy to better grasp his power; soldiers are sons, and sons are soldiers, they’re interchangeable. War is something that has to be taught to children, suffused into the family structure.

In her book The Remasculinization of America: Gender and the Vietnam War, Susan Jeffords argues that war is a gendering activity. She writes: “…a study of the structural relations between warfare and gender reveals them to be intimately connected, so much so that one does not survive without the other.” Men fight, and their worth as men directly corresponds with their ability to fight.

“On, on, you noblest English.

Whose blood is fet from fathers of war-proof!

Fathers that, like so many Alexanders,

Have in these parts from morn till even fought

And sheathed their swords for lack of argument:

Dishonour not your mothers; now attest

That those whom you call'd fathers did beget you.”

— Henry V, Act III, Scene I

House of the Dragon appears to agree; it (much like A Song of Ice and Fire) presupposes that to be born in this world is to be sacrificed to a gendered fate— women to die in childbirth, men to die in fields of blood. It turns its fascination not only to the deep harms this social structure visits on characters of all genders, but especially to those who ‘fail’ their genders, most notably the two warring monarchs themselves, Rhaenyra and Aegon. Neither make the ideal ruler in the Westerosi paradigm— Aegon’s performance of masculinity is so outward and farcical it rings false, and Rhaenyra is betrayed by the forcible assignation of her womanhood, all the gendered trappings thrust upon her that prove impenetrable.

Rhaenyra is beset with gender envy. She openly wishes she were a man, is pleased at being called ‘boy’, chafes at the constant expectations of womanhood that cage her. She is able to challenge these expectations to an extent, especially as she is raised the designated heir to the throne— a position seen as one only a man could hold. But only sometimes, and never without complications. Emma D’arcy portrays a simmering misery in how Rhaenyra must contort herself, a strange stilted way of moving and speaking, reading very much as dysphoric. Her counsellors don’t listen to her, openly wishing she would act more feminine so they could take over her decision-making. They transform her into a passive figurehead against her will. And she’s rendered most fascinating when she is forced to navigate and even perpetuate the gendered structures she despises and wishes she could transcend. (“Make this sacrifice willingly,” she says to Rhaena, conferring motherhood upon her, “for all of us.”) Can one take power in this world without becoming violent? Is there a masculinity without violence? Should you sell your soul to break your chains?

I found myself surprised by the show’s handling of Aegon. His relationship to masculinity was always sort of fraught— his sense of horror at the idea of taking power, his initial panicked flight from his coronation, his instinctual recoil from taking the throne that is his “right” by his gender, but his deep craving for it all the same. His masculinity always had to be proven, overcompensated for, via the weaponization of sexual violence against girls under his power, or other offences like the constant taunting of his brother. Masculinity is something so rotten and gnarled in him. It is his sense of emasculation (the worst imaginable fate, getting scoffed at by his mom, told that he is a passive figurehead himself, and nothing more) that prompts him to fly to battle, to prove himself a ‘true’ man yet again, and results in his disfigurement.

His is transformed deftly into a narrative of disability. Jeffords writes: “By emphasizing masculinity as a mechanism for the installation of patriarchal structure, it is possible to see the ways in which, through the structural relations of gender, men of color or of the working class or of other groups oppressed via defined categories of difference can be treated as women— “feminized”— and made subject to domination.” Of course this must include marginalization of disabled men as well, especially so in a martial society such as this, rendered ‘unmanned’ by their inability to contribute to society as warriors. Aegon is de-gendered by his disability— even if he weren’t quite literally de-sexed by it via the destruction of his genitalia. He is stripped of his kingship, his power, with Aemond taking over as regent, seen as just an inert body, useless, nothing.

It brings to mind a passage from Sarah Hagelins’ essay Bleeding Bodies and Post–Cold War Politics: Saving Private Ryan and the Gender of Vulnerability: “Saving Private Ryan […] makes the male body vulnerable, porous, and penetrable, focusing obsessively on this vulnerability the way few films of its genre do. The instability this creates around the gendered meanings of vulnerability threatens dominant cultural ideas about gender and war because it challenges an important assumption that even most antiwar films maintain: that society sends the strong (able-bodied men) to war in order to protect the weak or vulnerable (women, children, and nonmasculine men). This assumption allows the public to avoid the moral problem of war’s cost in broken bodies by imagining vulnerability primarily in the bodies left at home.”

War confers masculinity on its participants, confers power and control and dominance, but its horrific human cost cannot be acknowledged within this paradigm, creating a massive wave of cognitive dissonance. That’s what hounds Criston Cole, monologuing in monotone about the meaninglessness of his violent devotion, the utter waste, his white cloak soiled from the start. With Aegon, we see the paradigm utterly unravel. There is nothing heroic here, just a sad man destroyed by his own desperation to prove himself masculine. War leaves behind its victims, even the victorious ones, and there is no place for their cognitive or physical disability in a world where might makes right.

Enter Larys Strong, who is trying to unsubtly become Aegon’s main advisor. Why not try him when he’s at his weakest? He speaks to Aegon of his newfound disability, from the perspective of a man who has been castigated for his disability all his life. “People will pity you. Either behind your back or in your presence. And they will stare at you— at you— or turn away.” And then we see something very strange. Larys finds himself straining to speak. We see tears in his eyes— tears! From the cavalier murderer of his father and brother, from the overemployed torturer! There is a brief brilliant moment where they are wholly connected through their shared marginalization. And so much of it lies in the acting— Larys sounds earnestly surprised at how honest he’s being.

They form an uneasy alliance. Larys coordinates his partial recovery, then arranges his escape, correctly predicting an attack. He suggests Aegon become the Peacemaker, the Rebuilder… the Realm’s Delight, the former title of Rhaenyra. These accolades are not the masculine warrior ideal, but they have a certain power all the same. A power Larys understands and appreciates, a character who himself is de-gendered, “womanly” in his shadowy whisperings, undermined and underestimated and unpersoned (even by the writing of the show in its previous season). He’s always seemed to support the Greens because he genuinely likes their dysfunctional asses and finds them entertaining (and easily manipulated), but something deeper is formed here; they truly relate to one another on a level they’ve never found with anyone else. “I am burnt, and disgusting, and alone, and I am a cripple,” Aegon admits. Larys returns, “You’re not alone.”

It’s an odd storyline, especially concerning two characters so maligned by the audience, who are so actively malignant. But the narrative chooses to nevertheless make them round, real people, with a central shared experience of gender and disability that truly gives them hope in one another. Somehow, miraculously, they pull this off! It’s jaw-dropping television!

It’s a strange contrast to a season so haunted by its own meaninglessness. How many times can we hear each character lament that now the war has started, they cannot stop it? That it matters not who wins when the common people will starve and die equally under each regime, their comforts only part of a political calculus? That the dragons cannot be controlled? That the motivations for the fighting don’t matter, have never mattered, are superseded by the latest atrocity, which is then forgotten, over and over again? That though perhaps there were good intentions, once, and everyone can find a knot of justification within themselves, none of it really matters, none of it will ever matter? That everyone who speaks is doomed, and some of them know it full well?

It refuses to let up. There’s something very striking, even a bit brave, about its pessimism. Characters marinate in their utter hopelessness. Everyone broods. There is no catharsis in violence; it all just churns. We slowly zoom in on Alicent in a council meeting, disassociating, miserable, powerless, the justifications and feverish plans of the men around her rendered unintelligible by the sound design. Daemon spends the whole season in a torture chamber (we can’t even get into that right now). Criston walks like he’s already dead. “All our fine thoughts,” he murmurs, “all our endeavours are as nothing. We march now toward our annihilation. To die will be a kind of relief.”

It’s as if everyone— even those who lack precognitive powers— can see their fates written plainly.

In the final episode of the season, a new thread is woven in— one of metatextuality. It’s a little jarring when everyone starts very overtly mentioning story in every other line, but there’s something quite rich to it. The show’s intro, a change from last season’s rivers of blood, is now presented as a tapestry, the most striking images of the season’s events woven into history in real-time. The story thrums forward with no care for its victims. Daemon and Aemond are made utterly aware of their upcoming twinned deaths, and indeed stride towards them. Helaena and Alys are threaded into the fabric of the narrative, the fabric of time, prophesying dooms yet to come.

(In All Quiet on the Western Front (1930), perhaps the cinematic epitome of ‘war as tragedy’, one soldier dreams that the others are dead before it happens. Another starts the film writing the first act of a tragic play. War has often been portrayed as a space of precognition, of temporal displacement, its violence so extreme it ripples through time itself— see also: Cassandra.)

And Alicent— my beloved, cruel and frightened and bitter and longing Alicent!— feels her fate snap in two. Her part in this war, she realizes, has ended, she is meant to return to the wings. But this grants her an unfamiliar freedom. No one’s writing the lines for her anymore. In a not-so-shocking twist, she moves to prevent further bloodshed, cleaving to Rhaenyra, and sacrificing her son and his claim in the process. (It’s of course horrifically sad that the only way for her to reassert control over her own body and choices is to doom another.) Her only true desire now, she says, is to die unremarked and unnoticed and be free. Perhaps they can both escape this story now.

But Rhaenyra can never hope to die unremarked on as Alicent wishes, fated to face the most humiliating end of all— and even Alicent won’t be able to escape it, really, destined to waste away into a cruel husk, whispering for the old days. “My part is here, whether I will it or no,” says Rhaenyra, smiling sadly. “It was decided for me long ago.”

Every character is deeply trapped, diegetically in-world by other characters and social structures, but also trapped by the story itself, and then simultaneously by the histories constructed afterward, biased and incorrect as they may be, acting as just another cage. It’s difficult to be bothered by changes to the source material when the source material is already inconsistent by its nature, but the construction of that history is now presented as a tragedy and a horror in itself. The painful thing is not just that in large part these people fight for nothing, and only bring doom upon themselves and others, but that they’ll be remembered wrong forever, both in the world of the story… and by us. Fire and Blood’s faux-historical characterization of Alicent as a shrewish wicked stepmother and Rhaenyra as a gluttonous power-hungry slut now takes on a more fascinating bend, as we watch the real breathing women underneath the shells of the histories, clawing at the pages. It’s an incredibly keen way of adapting an epistolary narrative. The uncontrollability of war is directly linked to the uncontrollability of story itself.

Because war is a story. Above all, above even physical violence, war is most vitally a narrative. It is what we tell ourselves in order to justify the means, any means, any at all. Nations are stories, too. They are not real things that live and breathe. Rulers are stories— or they are forced to become them. Not a sentence, but an honour.

But for a person to become a story strips their personhood away utterly. Already their body is stripped from them, but ultimately the very idea of them is, too, all memory of them perverted. That becomes the central tragedy of the series— the war will be for nothing, no one will ‘win’ it, and even the histories will turn to caricatures, twisted and malformed, the arrogant princess and the wicked queen and the salacious whore, unable to even be granted decency in death, their stories stolen from them by the wizened men of the future who could never imagine a woman complexly. The records will never show the parts of themselves they sacrificed, nor even their motivations in doing so. The prophecy will be lost to the wind. The love will never have been there. It becomes a hostile challenge to the audience— will you assume the worst of these people, charged to witness the crushing vice of their circumstances? Are you warping their stories too?

Sacrifice your body. Sacrifice your children. Sacrifice your story. Sacrifice your memory. Fuck it, give it all to the crows. Isn’t that what war is— a massive blood sacrifice to bring about some dreamed cause?

Is it worth it?

Can it ever be?

As a silly little pacifist myself, I get unreasonably fucked up by war movies. Like, bad. Like I want to throw up the entire time and then I can’t sleep for days and walk around like a zombie consumed with misery about meaninglessness and waste. So it might sound a little weird for me to say that in many ways I find cinema about war the most life-affirming of all.

As George R. R. Martin might say: men’s lives have meaning, not their deaths.

And that’s where House of the Dragon’s second season manages to transcend itself— yes, these characters are hopeless, beaten down, destroyed by the wars they’ve wrought and fought, but they’re still scrabbling for life, for freedom, for a way out. Fruitlessly, painfully, they’re still human. They know well enough that none of it matters. Their fragile peaces can’t last. They were reared as sacrifices to a hungry patriarchy, and there’s no way out of the dragon’s gullet no matter their protests and machinations. But they’re alive. What else can they do?

“I do not wish to rule,” Alicent confesses, “I wish to live.” It’s performed as if it’s the first time she’s ever admitted that to herself. Aegon, in his painful throes, laments there is no point to his survival, as crippled as he is. Larys says, quietly, like he’s just now realizing it, “It’s best to live, I think. However you do it.”

Anti-war cinema (and in this case, television) succeeds on its determination that life, in all its fragility, has meaning. That is why we must witness its most wanton destruction, its systematic devaluation, the horror of its obliteration. At its best, it’s a sharp wailing cry of no more.

The Battle of Agincourt is never actually described in Henry V. We get the preparations, the aftermath, but we don’t see the fighting. The play’s rousing battle speeches, however, have been recited to motivate real soldiers since the 18th century, or at memorials, or utilized to promote war, or spoken in moments of great bravery by such storied men as George Washington, Charles Dickens, Winston Churchill, and the legal team arranging the presidential victory of George W. Bush. If it be a sin to covet honour, Henry says proudly, I am the most offending soul alive.

But all I can think about is the cost Henry describes at Harfleur. Cannons prying through the portage of the head, fair nature disguised for hard-favour’d rage. The child sacrificed for the man to be born.

Not a sentence, but an honour.